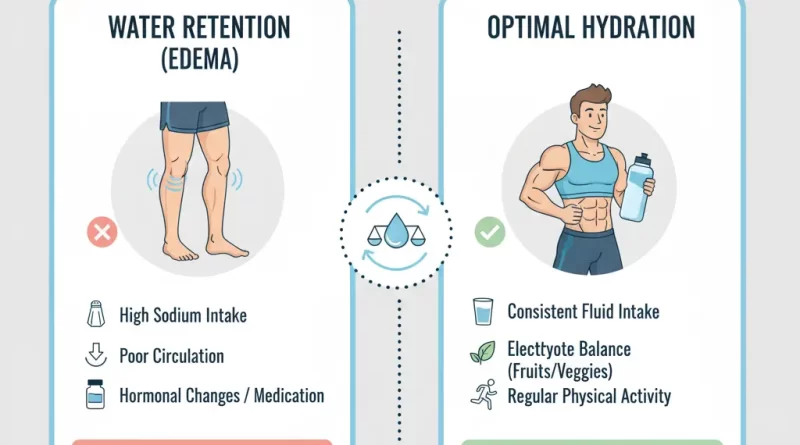

Water Retention and Hydration Levels: Understanding Daily Weight Fluctuations

If you’ve ever stepped on the scale one morning and noticed a sudden two- to five-pound increase, you’re not alone. Daily weight fluctuations are completely normal and are most often caused by changes in water balance, not body fat. Because water accounts for approximately 60% of your total body weight, even minor shifts in hydration can dramatically affect what the scale shows.

Understanding how and why your body retains or releases water can prevent unnecessary frustration during weight management, fitness programs, or fat-loss phases. This article explores the physiological mechanisms behind water retention, how diet and lifestyle influence it, and strategies to maintain consistent hydration for optimal health and performance.

Why Water Matters

Water is fundamental to life and vital for nearly every physiological process. It regulates body temperature, transports nutrients, flushes waste, lubricates joints, and supports metabolic reactions. A stable water balance—where fluid intake equals fluid loss—is essential for both performance and health.

However, several dietary and lifestyle factors can disrupt this balance and lead to temporary water retention or dehydration, both of which can influence your daily body weight readings.

Sodium Intake and Water Retention

How Sodium Affects Fluid Balance

Sodium is one of the body’s key electrolytes, and it plays a crucial role in maintaining osmotic pressure—the movement of water between cells and blood plasma. When sodium intake increases, the body retains water to keep the sodium-to-water ratio stable.

For instance, after a particularly salty meal, your blood sodium concentration rises. In response, your kidneys slow down sodium excretion and retain water to dilute the excess. This results in temporary weight gain and mild puffiness, often noticeable in the face, fingers, or ankles.

The Typical Impact

A salty meal can cause your body to hold onto 2–5 pounds (1–2.5 kg) of additional water overnight. This does not reflect true fat gain but rather a short-term increase in extracellular fluid.

The Solution

- Stay consistent with daily sodium intake. Drastic fluctuations can cause your body to “chase equilibrium,” leading to variable water retention.

- Hydrate adequately. Ironically, drinking more water helps your body flush out excess sodium through urine.

- Limit processed foods, which are often high in hidden sodium sources such as sauces, deli meats, and snacks.

Carbohydrate Intake and Glycogen-Linked Water Storage

The Glycogen-Water Connection

Carbohydrates are stored in the body as glycogen—a form of energy reserve located in the muscles and liver. Each gram of glycogen binds approximately 3 grams of water (Olsson & Saltin, 1970).

This relationship means that fluctuations in carbohydrate consumption can significantly alter your short-term body weight. For example, if you consume an additional 300 grams of carbohydrates, your body could store about 900 grams (nearly 2 pounds) of water along with the glycogen.

Why You May Notice Scale Changes

- After High-Carb Days: Your weight may rise 1–3 pounds due to increased glycogen and water storage.

- After Low-Carb or Keto Dieting: Glycogen stores decrease, leading to rapid “water weight” loss during the first week. This can make early weight loss seem dramatic but is mostly fluid-based, not fat-based.

Athletic and Performance Implications

For endurance athletes or strength trainees, glycogen-related water retention isn’t negative—it’s functional hydration. Well-hydrated muscles with adequate glycogen perform better, resist fatigue longer, and recover more efficiently.

Dehydration and Its Weight Effects

Why Dehydration Reduces Scale Weight

When you sweat heavily during exercise or fail to replace lost fluids, your body weight drops temporarily due to water loss. However, this decrease is not an indicator of fat loss. Dehydration can reduce plasma volume, impair thermoregulation, and negatively affect cardiovascular performance.

Signs of Dehydration

- Dark yellow urine

- Fatigue or dizziness

- Headaches

- Dry mouth and lips

- Muscle cramps during exercise

The Rebound Effect

Once you rehydrate, your body naturally restores fluid balance, causing your scale weight to rebound to normal levels. This explains why post-exercise or post-sauna weigh-ins often appear artificially low.

Hydration Guidelines

- Aim for 30–35 ml of water per kilogram of body weight daily (roughly 2.5–3.5 liters for most adults).

- Increase intake during hot weather or intense exercise.

- Include electrolytes when sweating heavily for prolonged periods to replace sodium and potassium losses.

Hormonal Influences on Water Retention

Cortisol and Stress

Chronic stress elevates cortisol levels, which can promote fluid retention by altering kidney function and sodium balance. This is why people under high stress may experience bloating and temporary weight increases despite unchanged diet or training.

Estrogen and Progesterone

In women, hormonal fluctuations during the menstrual cycle can cause significant water retention, especially in the luteal phase (days leading up to menstruation). Weight may fluctuate by 1–4 pounds during this period, returning to baseline once hormone levels stabilize.

Hydration, Exercise, and Performance

Proper hydration directly impacts muscular endurance, power output, and thermoregulation. Even a 2% drop in body weight from fluid loss can impair performance and cognitive function (Sawka et al., 2007).

During Exercise

- Drink small, frequent sips of water throughout your workout.

- For sessions lasting over 60 minutes, consider a sports drink with sodium and carbohydrates to maintain fluid balance.

Post-Workout Rehydration

Replenish fluids based on sweat loss—roughly 1.5 liters of water per kilogram of weight lost during training (Casa et al., 2000). Including electrolytes aids more complete rehydration and prevents post-exercise fatigue.

Debunking Common Myths About Water Weight

Myth 1: “Drinking more water makes you bloated.”

Truth: Consistent hydration actually reduces bloating. When you drink enough, your kidneys efficiently regulate sodium, preventing unnecessary fluid retention.

Myth 2: “Water weight is bad.”

Truth: Water weight is essential for metabolic health and muscular function. Rapid water loss through extreme diets or diuretics can harm performance and cardiovascular stability.

Myth 3: “The scale reflects fat gain or loss directly.”

Truth: The scale reflects total body mass, including water, glycogen, and food volume. A few pounds up or down day-to-day rarely represent actual changes in body fat.

Practical Strategies for Managing Water Retention

- Stay Hydrated Consistently: Aim for steady water intake throughout the day instead of over-consuming at once.

- Keep Sodium Steady: Avoid dramatic fluctuations in salt intake from one day to the next.

- Balance Carbohydrates: Recognize that carb refeeding or depletion impacts short-term weight, not long-term fat loss.

- Prioritize Potassium-Rich Foods: Bananas, spinach, sweet potatoes, and avocados help balance sodium and reduce bloating.

- Manage Stress: Incorporate relaxation techniques like deep breathing, yoga, or mindfulness.

- Track, Don’t Obsess: Weigh yourself at the same time daily, under consistent conditions, to spot meaningful trends rather than daily variations.

Takeaway

A sudden jump on the scale after a pizza or pasta night doesn’t mean you’ve gained fat—it’s your body storing water alongside sodium and glycogen. Similarly, a quick drop after intense exercise or a low-carb day is often due to dehydration, not true fat loss.

Understanding how water retention and hydration work allows you to interpret scale changes more accurately and avoid unnecessary discouragement. The key is maintaining consistent hydration, balanced electrolytes, and steady nutrition habits—the foundation for optimal performance, recovery, and health.

References

- Olsson, K. E., & Saltin, B. (1970). Variation in total body water with muscle glycogen changes in man. Acta Physiologica Scandinavica,